In the vast and diverse world of social impact, “nonprofit” and “NGO” are terms often used interchangeably. Yet, they are not quite the same. Understanding the distinction between a traditional nonprofit organization and an international non-governmental organization (INGO) is crucial for practitioners, donors, policymakers, and anyone passionate about driving global change.

Both entities are mission-driven, both operate outside of government control, and both are vital in addressing humanitarian, environmental, social, and economic challenges. But their scale, scope, structure, and regulatory frameworks diverge in meaningful ways.

Defining the Terms

- Traditional Nonprofit Organization: A nonprofit organization (NPO) is generally a legal entity operating within a specific country, recognized under domestic nonprofit or charitable laws. It reinvests any surplus revenue back into its mission, rather than distributing profits to shareholders. Most traditional nonprofits operate locally or nationally, serving communities within the same country where they are registered.

- International Non-Governmental Organization (INGO): An INGO operates across national borders, often with programs in multiple countries. INGOs typically address transnational issues—human rights, humanitarian aid, environmental sustainability, global health—and work through a combination of field offices, global staff, and partnerships with local organizations. They must navigate a complex web of international law, cross-border taxation, foreign bank transfers, and donor compliance protocols.

Scope and Reach

The most immediate difference lies in scale.

Traditional nonprofits tend to focus on a city, region, or country. For example, a food bank in Chicago or a literacy nonprofit in rural India is typically limited by its national registration and local funding sources. These nonprofits often have intimate knowledge of their communities, a grassroots presence, and the ability to be nimble in local advocacy.

International NGOs like Habitat for Humanity, the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), or Médecins Sans Frontières operate in dozens of countries with global budgets, international staff, and multilayered governance. Their reach may span disaster relief in Haiti, housing in Cambodia, and environmental policy in the European Union—all coordinated through centralized leadership structures and in-country partners.

Governance and Compliance Requirements

NPOs are typically governed by domestic nonprofit laws. For example, in the United States, they might be 501(c)(3) organizations overseen by the IRS and required to file annual Form 990s.

INGOs must meet regulatory standards not only in their home country (often where they are incorporated and fundraise), but also in each country where they operate. This means:

- Registering with local authorities in host countries

- Complying with anti-terrorism financing laws (e.g., OFAC in the U.S.)

- Meeting GDPR or equivalent privacy rules in data handling

- Navigating foreign bank account regulations, exchange control laws, and local tax withholding rules

Compliance failures can lead to serious consequences, from frozen bank accounts to blacklisting by governments.

Funding and Donor Requirements

Local nonprofits often rely on domestic donations, government grants, or local foundations. Their fundraising strategies tend to be community-based—galas, donor campaigns, or city grants.

By contrast, INGOs are often funded by multilateral institutions (e.g., UN, EU, World Bank), bilateral development agencies (e.g., USAID, DFID), large philanthropic foundations, and major private donors. These sources come with stringent reporting requirements. INGOs must produce detailed impact evaluations, audit-ready financials, environmental assessments, and human rights due diligence.

According to Devex’s 2023 Donor Trends Report, the average reporting requirement for an INGO grant exceeds 50 pages annually, with more than half of donors requiring quarterly updates.

Staffing and Organizational Structure

A traditional nonprofit might have a small team—paid staff, volunteers, and a board of directors. Their hierarchy is often flat, and their focus narrow. They are agile but can be stretched thin.

INGOs require complex staffing models, often with:

- Headquarters in one country (e.g., Switzerland, U.K., U.S.)

- Regional hubs in Africa, Asia, Latin America

- Country-specific offices with local hires and project managers

Managing HR across jurisdictions adds legal and cultural complexity. Contracts must comply with local labor laws, and INGOs must address security protocols, language barriers, and remote management challenges.

Community Engagement and Localization

Smaller nonprofits often have deep local roots—they emerged from the community and reflect its needs. This is a key strength.

Large INGOs have been criticized for being too top-down, exporting Western development models without adequate community input. In response, many INGOs are shifting toward localization—partnering with or transitioning authority to local organizations.

The “Grand Bargain” agreement in the humanitarian sector commits INGOs to pass at least 25% of funding directly to local actors by 2025. Change is slow but visible: organizations like Oxfam and Save the Children are publicly decentralizing operations to align with this movement.

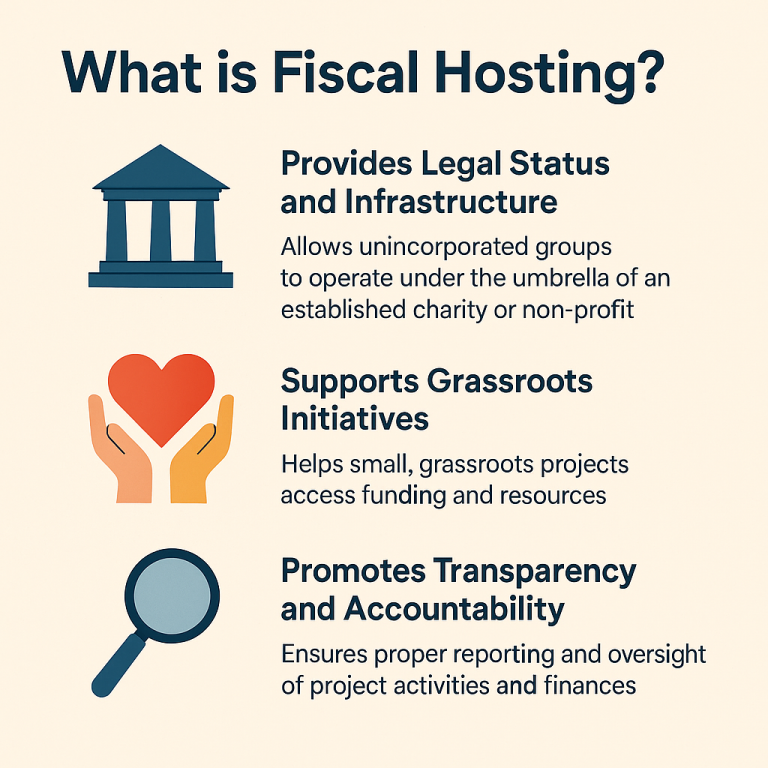

Accountability and Transparency

Traditional nonprofits are often held accountable by local donors, media, and community feedback. They may post impact reports online or share updates via newsletters.

INGOs face a different level of scrutiny—from global watchdogs, host governments, and multi-year audits. Platforms like the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) provide public data on their funding, outputs, and results.

Conclusion: Different Models, Shared Purpose

The difference between a traditional nonprofit and an international NGO lies in more than geography—it’s about structure, capacity, compliance, and funding scale. Yet both play critical roles in the social change ecosystem.

Traditional nonprofits bring closeness, cultural fluency, and community trust. INGOs bring resources, policy influence, and technical expertise. The most effective global change happens when the two collaborate—each leveraging their strengths to serve the world’s most urgent needs.

Whether you’re supporting a grassroots food justice project in Detroit or an international climate campaign, knowing the distinctions between these models helps donors, practitioners, and policymakers align resources wisely—and build a more just and effective civil society.

References

- Devex (2023). Donor Trends and Reporting Demands

- Stanford Social Innovation Review (2024). NGO Structures and Localization

- International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) (2023). Global Reporting Standards

- Center for Effective Philanthropy (2024). Nonprofit Governance Trends

- OECD (2023). International NGO Compliance and Taxation Brief

- USAID (2023). Guidelines for Local and International NGO Collaboration

- Oxfam (2024). Localization and Decentralization Strategic Plan